Wandering salamanders control blood flow in their toes to improve adhesion and detachment, a finding that could inspire new adhesive and robotic technologies.

The wandering salamander is known for its ability to glide high above the canopy of coastal redwood forests, but how the small amphibian can land and take off with such ease remains a mystery.

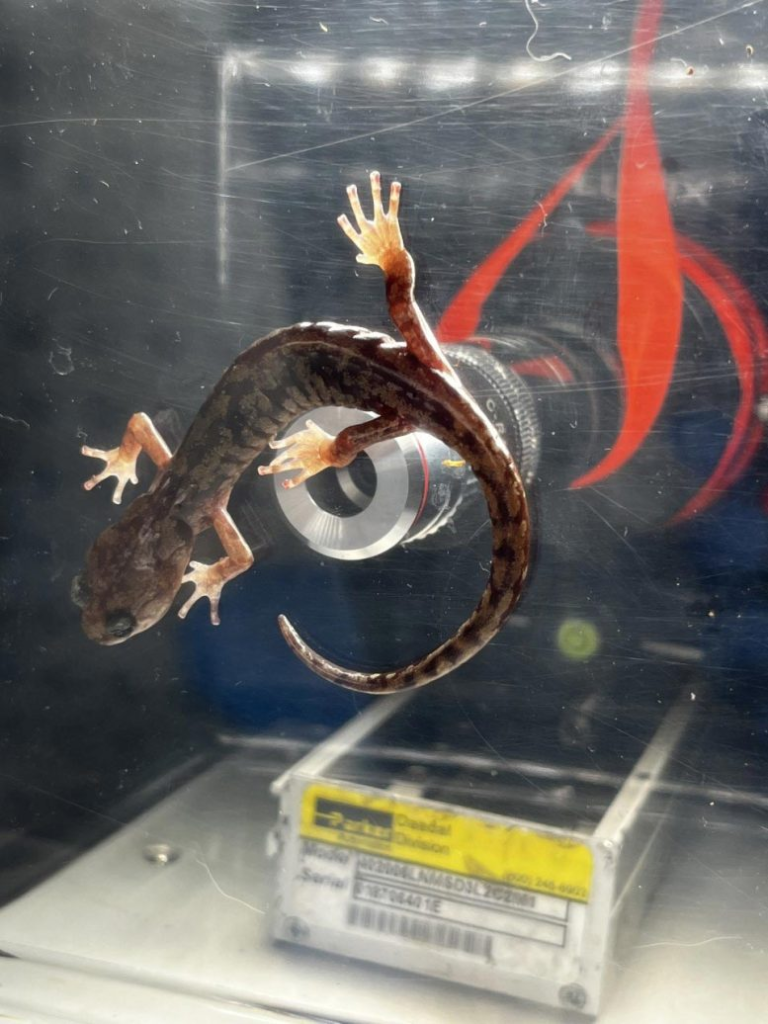

A new study in the Journal of Morphology suggests that the answer may lie in a surprising mechanism: toes are powered by blood. Washington State University-led researchers have discovered that the wandering salamander ( Aneides vagrans ) can rapidly fill, retain, and pump blood from the tips of its toes, optimizing grip, separation, and overall locomotion in its arboreal habitat.

The research not only reveals a previously unknown physiological mechanism in salamanders, but also has implications for bio-inspired design. Insights into the mechanism of the salamander’s finger could ultimately lead to the development of adhesives, prosthetics, and even robotic appendages.

“The lizard-inspired adhesive allowed the surface to be reused without losing its stickiness,” said Christian Brown, lead author of the study and a postdoctoral researcher in integrative physiology and neuroscience at WSU. “Understanding salamander fingers could lead to similar breakthroughs in attachment technology.”

Discovery sparked by documentary filming

Newts of the genus Aneides have long puzzled scientists with their square toes and bright red “lakes” of blood visible just beneath their transparent skin. Traditionally, these features were thought to aid in oxidation, but there is no evidence to support this claim.

Brown’s interest in the subject stemmed from a surprising observation while filming the documentary “The Americas,” which airs Feb. 23 on NBC and Peacock. While assisting on the set as the resident salamander expert, Brown had the opportunity to observe the amphibians moving through the lens of the production team’s powerful cameras.

He noticed something strange. Blood flows into the transparent toes of these tiny creatures just before they walk. Brown and camera assistant William Goldenberg kept watching the phenomenon. “We looked at each other like, ‘Did you see that?'” Brown said.

Although the producers moved on, Brown’s curiosity did not. After filming was completed, he contacted Goldenberg and asked if he would like to use his filming equipment to scientifically and repeatably examine what they had observed.

Through high-resolution video experiments and verification analysis at WSU’s Franceschi Microscopy and Imaging Center, Brown, Goldenberg and colleagues from WSU and Gonzaga University found that wandering salamanders can precisely control and regulate blood flow to each side of their toes.

This allows them to apply pressure asymmetrically, improving grip on uneven surfaces such as tree bark. Surprisingly, the rush of blood before the “step” appears to help the salamander release rather than hold on. By slightly inflating the tips of its toes, the salamander reduces the surface area in contact with the surface it is gripping, minimizing the energy required to release. This maneuver is essential for navigating the uneven and slippery surfaces of the redwood canopy—and for landing safely when jumping between branches.

“If you’re climbing a redwood tree and you have 18 fingers on the bark, being able to effectively separate yourself without damaging your fingertips makes a huge difference,” says Brown.

The implications of the study may extend beyond Aneides vagrans . Similar vascular structures are found in other salamanders , including aquatic species, suggesting a common mechanism for regulating toe stiffness that may serve different purposes depending on the salamander’s environment. Brown and colleagues plan to expand the study to see how the mechanism works in other salamander species and habitats.

“This could redefine our understanding of how salamanders move across different habitats,” Brown said.

Reference: “Vascular and skeletal morphology of an elongated fingertip reveals specialization in a mobile salamander (Aneides vagrans)” by Christian E. Brown, William P. Goldenberg, Olivia M. Hinds, Mary Kate O’Donnell, and Nancy L. Staub, January 8, 2025, Journal of Morphology .

Hi tenyten.com Administrator