The roundworm C. elegans is a simple animal with a nervous system containing just 302 neurons. Each connection between these neurons has been comprehensively mapped, allowing researchers to study how they work together to produce a variety of animal behaviors.

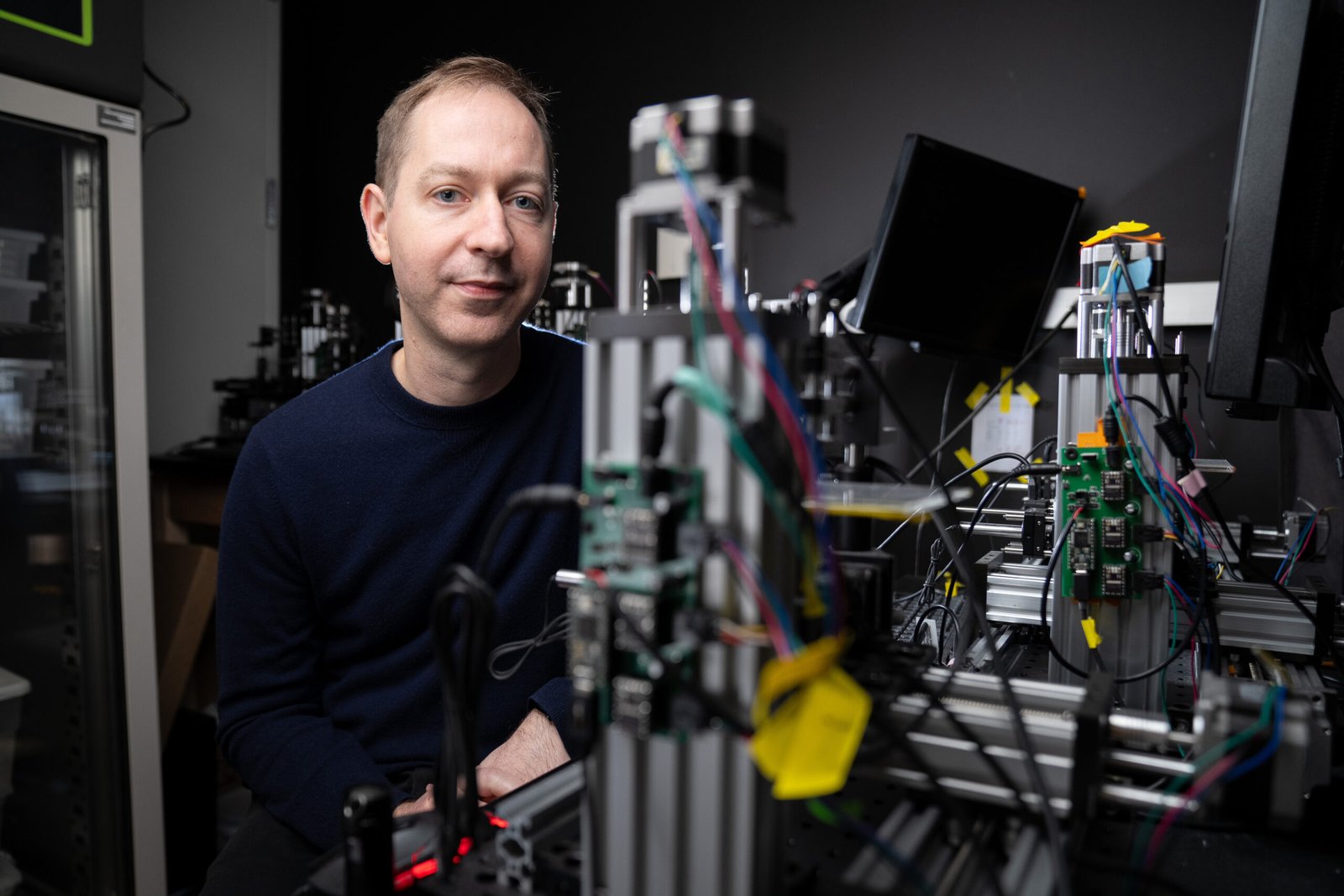

Steven Flavel, an associate professor of brain and cognitive sciences at MIT and an investigator at MIT’s Picower Institute for Learning and Memory and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, uses the worms as a model to study motivated behaviors, such as feeding and navigation, with the goal of uncovering the underlying mechanisms that determine how similar behaviors are controlled in other animals.

In recent studies, Flavel’s lab has uncovered the neural mechanisms behind adaptive changes in the feeding behavior of nematodes and also mapped how the activity of individual neurons in the animal’s nervous system affects different behaviors of the nematode.

Such studies could help researchers better understand how brain activity produces human behavior. “Our goal is to identify neural circuits and molecular mechanisms that can be generalized across organisms,” he said, noting that many fundamental biological discoveries, including those related to programmed cell death, microRNAs and RNA interference, were first made in C. elegans .

“In our lab, we primarily study behaviors that depend on motivated states, such as eating and navigation. The mechanisms used to control these states inC. elegans (neuromodulators, for example) are in fact the same as those in humans. These pathways have deep evolutionary origins,” he said.

Attracted by the research lab

Flavel was born in London to an English father and a Dutch mother, and moved to the United States at age two when his father became Biogen’s chief scientific officer in 1982. His family lives in Sudbury, Massachusetts, where his mother works as a computer programmer and mathematics teacher. His father later became a professor of immunology at Yale University.

Flavel grew up in a family of scientists, but when he enrolled at Oberlin College, he planned to major in English. As a musician, Flavel took jazz guitar classes at the Oberlin Conservatory and also plays piano and saxophone. But after taking classes in psychology and physiology, he realized that neuroscience was the field he was most passionate about.

“I was immediately sold on neuroscience,” he said. “It combines the rigor of biology with the deep questions of psychology.”

During college, Flavel worked on a summer research project on Alzheimer’s disease in a lab at Case Western Reserve University. He then continued the project, which involved post-mortem analysis of Alzheimer’s tissue, during his senior year at Oberlin College.

“My first research was on disease mechanisms. My research interests have evolved since then, but it was my first research experience that really got me hooked on lab work — doing experiments, seeing completely new results and trying to understand them,” he says.

By the end of his college years, Flavel considered himself a lab rat. “I just liked being in the lab.” He applied to graduate school and eventually went on to Harvard Medical School to earn a PhD in neuroscience. Flavel collaborated with Michael Greenberg to study how sensory experience and the resulting neural activity affect the developing brain. In particular, he focused on a family of regulatory genes called MEF2, which play a key role in neuronal development and synaptic plasticity.

All of these studies were done in mouse models, but Flavel switched to working with C. elegansduring his postdoctoral research with Cori Bergman at Rockefeller University . He was interested in studying how neural circuits control behavior, which seemed more feasible in a simpler animal model.

“Studying how neurons throughout the brain control behavior seems nearly impossible in a large brain. Understanding all the fundamental details of how neurons interact and ultimately produce behavior seems like a daunting task,” he says, “but I was immediately excited to study this inC. elegans because, at the time, it was the only animal that had a complete blueprint of the brain – a map of all the brain cells and how they are connected to each other.”

This wiring diagram includes about 7,000 synapses throughout the nervous system. By comparison, human neurons can form more than 10,000 synapses. “Compared to those larger systems, the C. elegans nervous system is extremely simple,” Flavel says.

Despite their very simple structure, roundworms are capable of complex behaviors such as feeding, moving and laying eggs. They also sleep, form memories and find suitable mates. The neuromodulators and cellular mechanisms that generate these behaviors are similar to those found in humans and other mammals.

“C. elegans is an attractive subject to study because it has a small set of pretty well-defined behaviors,” Flavel said. “You can actually measure and study just about every behavior in this animal.”

How behavior occurs

Early in his career, Flavel’s work with C. elegans uncovered the neural mechanisms underlying the animal’s stable behavioral states. When earthworms forage for food, they alternate between steadily exploring their environment and stopping to eat. “The speed at which they switch between these states depends heavily on all sorts of signals in the environment,” Flavel says. Is the feeding environment good? How hungry are they? Are there smells that indicate a better food source is nearby? The animals integrate all that and adjust their foraging strategy.”

These stable behavioral states are controlled by neuromodulators such as serotonin. By studying serotonin’s regulation of behavioral states in nematodes, Flavell’s lab was able to discover how this important system is organized. In a recent study, Flavell and his colleagues published an “atlas” of the serotonin system in C. elegans . They identified all the neurons that produce serotonin, all the neurons that have serotonin receptors, and revealed how the animals’ brain activity and behavior change when serotonin is released.

“Our work on how the serotonin system controls behavior has revealed fundamental aspects of serotonin signaling that may be generalizable to mammals,” Flavel said. “By studying how the brain achieves these long-lasting states, we will be able to exploit these fundamental features of neuronal function. The resolution we can achieve in studying specific C. elegans neurons and theirbehavior allows us to reveal fundamental features of how neurons work.”

In parallel, Flavel’s lab has also uncovered how neurons in the C. elegans brain control different aspects of behavior. In a 2023 study, Flavel’s lab mapped how changes in activity throughout the brain relate to behavior. His lab uses a specialized microscope that moves alongside the exploring worms, allowing them to simultaneously track all of their behavior and measure the activity of every neuron in the brain. The researchers leveraged this data to create computational models that can precisely capture the relationship between brain activity and behavior.

Flavel said this kind of research requires expertise in many fields. In searching for a faculty position, he wanted to find a place where he could collaborate with researchers working in different areas of neuroscience, as well as scientists and engineers from other departments.

“Working at MIT has made my lab much more interdisciplinary than it has been elsewhere,” he says. “Everyone in my lab has undergraduate degrees in physics, mathematics, computer science, biology, and neuroscience, and we use tools from all of those fields. We design microscopes, we build computational models, and we devise molecular tricks to perturb neurons inthe C. elegans nervous system . And I think being able to deploy all these kinds of tools will lead to some fascinating research results.”