If there’s one common thread among Sidney Dolan’s goals, it’s a strong belief in being a better manager, in space and on Earth.

As a doctoral student at the MIT School of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AeroAstro), Dolan is developing models aimed at mitigating satellite collisions. They see space as a public good, a resource for everyone. “There is a real concern that if enough collisions occur, the entire orbit could be contaminated,” they said. “We need to be very careful to make sure that people have access to it, and that we can use space for the various uses that exist today.”

At Blue Planet, Dolan is passionate about building community and ensuring students in the department have what they need to be successful. To achieve that goal, they have invested heavily in mentoring other students; leading and participating in interest groups for women and the LGBTQ+ community; and creating media resources to help students navigate their graduate programs.

Expanding into new territories

Dolan’s passion for aerospace began when he was a high school student in Centreville, Virginia, when a close friend invited them to a model rocketry club meeting because she didn’t want to go alone. “I ended up going with her and really enjoyed it, and it became more of a hobby than just hers!” they laugh. The experience of building and launching rockets in rural Virginia gave Dolan hands-on and formative experience in aerospace engineering, and convinced him to pursue the field in college.

They were drawn to Purdue by its beautiful aerospace building and its status as a premier astronaut training site, and while they are grateful for the education they received there, it was clear to see that there were no other women on the faculty.

This gender imbalance prompted Dolan to found Purdue Women in Aerospace to foster networking and change the culture of the aerospace department. The group worked to create a more welcoming learning space for women and organized the first annual Amelia Earhart Summit to celebrate women’s contributions to the field. Hundreds of students, alumni and others gathered for a day filled with inspiring talks, academic and industry workshops and networking opportunities.

During their junior year, Dolan was accepted into the Matthew Isacowitz Fellowship Program, which places students in jobs at commercial space companies and pairs them with a career counselor. They interned at Nanoracks over the summer, developing a small cubesat payload to send to the International Space Station. Through the internship, they met Natalya Bailey (Class of 2014), a former doctoral student in MIT’s Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics. With Dolan considering graduate school, Bailey gave him valuable advice on where to apply and what to include in his application, as well as recommending MIT.

He applied to other schools, but MIT stood out. “At that point, I wasn’t really sure whether I wanted to specialize in systems engineering or guidance, navigation, control, and autonomy,” Dolan explains. “And I really like that MIT’s program has strengths in both areas,” he says, adding that very few schools have both majors. That way, he’d always have the option to change majors if his interests changed.

Becoming a good space actor

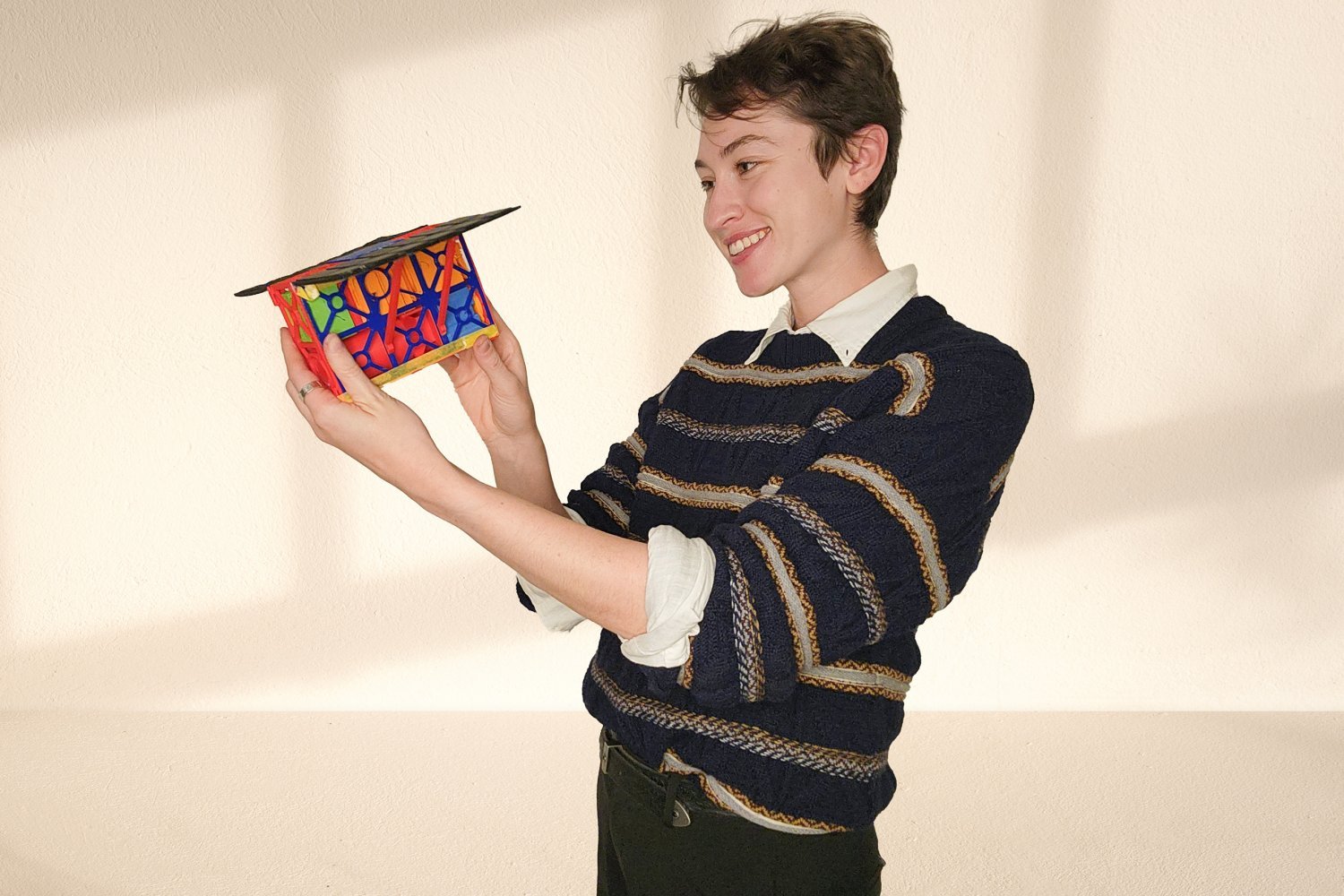

That option helps. For their master’s degrees, they carried out two research projects in the field of systems engineering. In their first year, they joined the Engineering Systems Laboratory to compare lunar and Mars mission architectures to determine which technologies could be successfully deployed on both the Moon and Mars that were, in Dolan’s words, “the most cost-effective.” Next, they worked on the Media Lab’s TESSERAE project, which aims to create cells that can autonomously self-assemble to form science labs, zero-gravity habitats, and other applications in space. Dolan studied cell control and the feasibility of using computer vision on cells.

Dolan eventually decided to shift the focus of his doctoral studies to autonomy, focusing on satellite transportation applications, and they joined the DINaMo research group, collaborating with Hamsa Balakrishnan, associate dean of the School of Engineering and the William Leonhardt (1940) Professor of Aerospace Engineering.

Space traffic management is becoming increasingly complex. As the cost of going to space fell and new launch providers like SpaceX emerged, the number of satellites has increased over the past few decades, as has the risk of collision. Satellites moving at about 17,000 miles per hour can cause catastrophic damage and create debris that can pose further hazards. The European Space Agency estimates that there are about 11,500 satellites in orbit (2,500 of which are out of service) and more than 35,000 pieces of debris larger than 10 cm. Last February, a NASA satellite and a defunct Russian reconnaissance satellite nearly collided, just 33 feet apart.

Despite these risks, there is no central regulatory body overseeing satellite operations, and many satellite operators are reluctant to share the exact locations of their satellites, although they do provide limited information, Dolan said. Their doctoral thesis aims to address these issues through a model that allows satellites to make autonomous decisions about collision avoidance maneuvers, using information gathered from nearby satellites. Dolan’s approach is interdisciplinary, using reinforcement learning, game theory and optimal control to abstract a graphical representation of the spatial environment.

Dolan sees the model as a potential tool to provide decentralized oversight and inform policy: “I’m primarily just advocating for treating space as a protected resource, like a national park, and being good stewards of space. And we have the mathematical tools we can use to actually test whether this kind of information is useful.”

Finding a natural fit

Now completing her fifth year, Dolan has been heavily involved in the MIT AeroAstro community since she arrived in 2019. She has served as a peer mediator in the dREFS (Faculty Resources for Reducing Friction and Stress) program; mentored other female students; and co-chaired the Women in Aerospace Engineering Graduate Group. As a communications researcher in the AeroAstro Communications Lab, Dolan created and provided workshops, training activities, and other resources to help students write journal articles, scholarship applications, posters, resumes, and other scientific communication formats. “I firmly believe that everyone should have the same resources to be successful in graduate school,” Dolan said. “MIT is really great in terms of providing a lot of resources, but it can be difficult to figure out what they are and who to ask.”

In 2020, they helped found an LGBTQ+ interest group called QuASAR (Queer Supportive Space in AeroAstro). Unlike most MIT clubs, QuASAR is open to everyone in the department: undergraduates, graduate students, faculty, and staff. Members meet for social events several times a year, and QuASAR has hosted academic and industry conferences to better reflect the diversity of identities in the aerospace field.

In their spare time, Dolan enjoys running ultramarathons, or distances longer than a full marathon. So far, they’ve run 50k and 50-mile races, and recently ran a 120-mile ultramarathon in their backyard (“basically running until you drop,” Dolan says). It’s a great stress reliever, and oddly enough, the ultramarathon field has found a lot of doctoral students. “I mentioned this to a counselor once, and she said, ‘Sydney, you’re crazy. Why would you do that?’ And she said it very politely! And I thought, ‘Well, why would I want to do something that has a vague end date and requires so much hard work and discipline?'” Dolan says, grinning.

As they prepare to finish their journey at MIT, their hard work and discipline will pay off. After earning his degree, Dolan hopes to take up a teaching position at the university. Becoming a professor seemed like a natural progression, combining their passion for aerospace engineering with their passion for teaching and mentoring, they said. As for where they might go, Dolan was philosophical: “I’m throwing a lot of darts at the wall, and we’ll see what space takes.”