Although all cells in the body contain the same sequence of genes, each cell expresses only a subset of those genes. These cell-specific gene expression patterns that ensure that a brain cell is different from a skin cell are determined in part by the three-dimensional structure of the genetic material that controls the accessibility of individual genes.

MIT chemists have devised a new way to use generative artificial intelligence to identify 3D genome structures. The technique can predict thousands of structures in just a few minutes, far faster than existing experimental methods for analyzing the structures.

Using this technique, researchers can easily study how the 3D organization of the genome affects the function and gene expression patterns of individual cells.

“Our goal is to predict the three-dimensional genome structure from the underlying DNA sequence,” said Bin Zhang, associate professor of chemistry and lead author of the study. “Now that we can do that, bringing this technology up to par with state-of-the-art experimental techniques could really open up a lot of exciting opportunities.”

The lead authors of the paper published today in the journal Science Advances are MIT graduate students Greg Schuette and Zhuohan Rao .

From sequence to structure

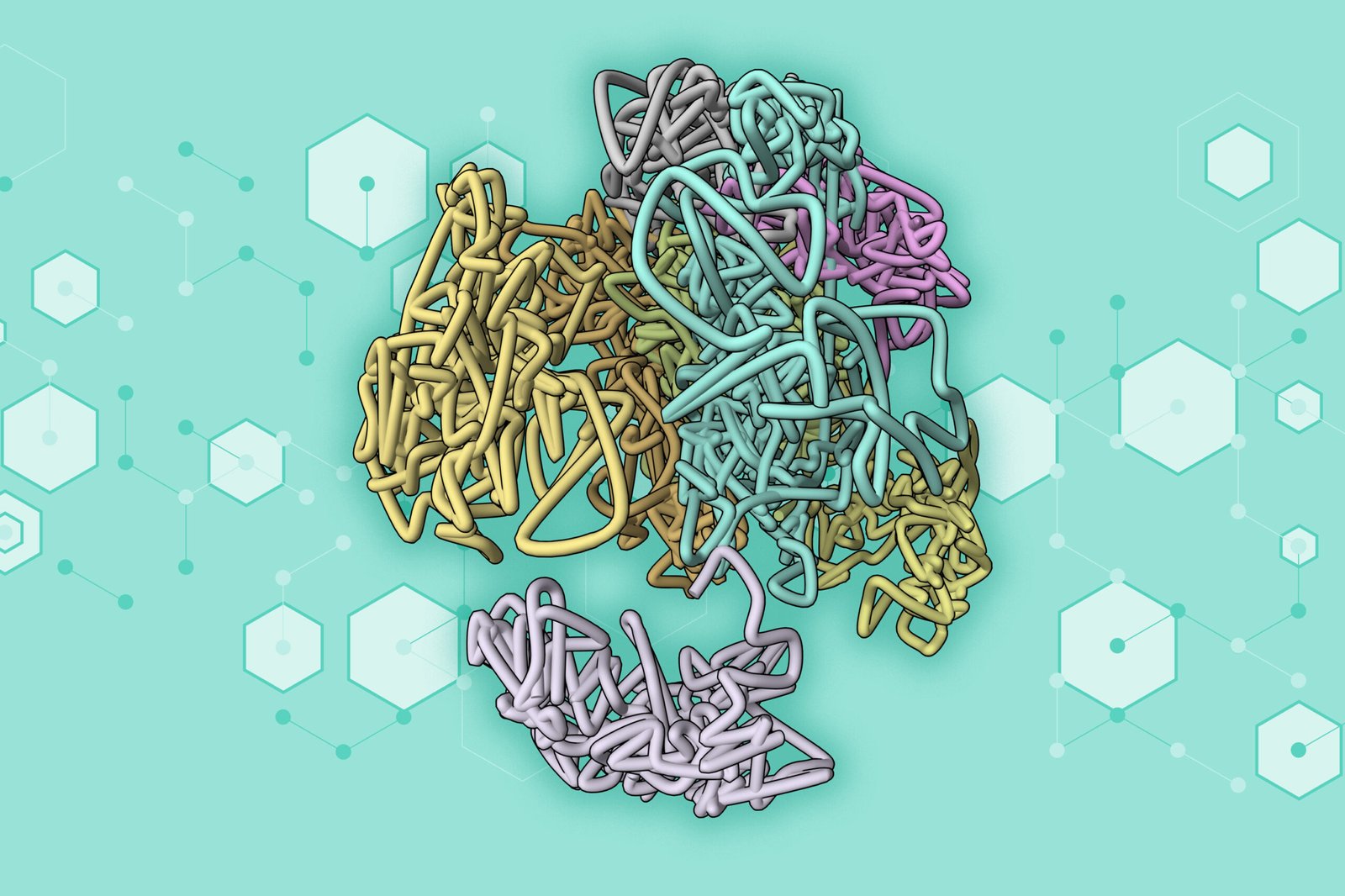

Within the cell nucleus, DNA and proteins form a complex called chromatin that has multiple levels of organization, allowing a cell to pack two metres of DNA into a nucleus just a hundredth of a millimetre in diameter. Long strands of DNA are wrapped around proteins called histones, forming structures that look like beads on a string.

Chemical tags called epigenetic modifications can be added to DNA at specific locations, and these tags, which vary depending on the cell type, affect the folding of chromatin and the accessibility of nearby genes. These differences in chromatin organization can help determine which genes are expressed in different cell types, or which genes are expressed at what time within a particular cell.

Over the past two decades, scientists have developed laboratory techniques to determine chromatin structure. One widely used technique, Hi-C, works by joining adjacent strands of DNA in a cell’s nucleus. By chopping the DNA into small pieces and sequencing it, researchers can determine which segments are close together.

This method can be used for large populations of cells to calculate the average structure of a section of chromatin, or for single cells to determine the structure within that particular cell. However, Hi-C and similar techniques are labor intensive and can take approximately a week to generate data from a single cell.

To overcome these limitations, Zhang and his students developed a model that leverages recent advances in generative AI to create a fast, accurate way to predict chromatin structures within single cells. The AI model they designed can rapidly analyze DNA sequences and predict the chromatin structures those sequences are likely to create inside cells.

“Deep learning is very good at pattern recognition,” Zhang says, “which makes it possible to analyze very long stretches of DNA, up to thousands of base pairs, and discover the important information encoded in those DNA base pairs.”

The model the researchers created, called “ChromoGen,” has two components: The first is a deep learning model that is taught to “read” the genome, analysing the information encoded in the underlying DNA sequence as well as widely available, cell-type-specific chromatin accessibility data.

The second component is an AI model that is trained on over 11 million chromatin configurations to generate physically accurate predictions of chromatin configurations. These data were generated from experiments using Dip-C (a variant of Hi-C) on 16 cells from a human B-lymphocyte cell line.

When integrated, the first components inform the germline model about how cell-type-specific environments affect the formation of different chromatin structures, and the scheme effectively captures the relationship between sequence and structure. For each sequence, the researchers used the model to generate many possible structures. This is because DNA is a highly disordered molecule, so many different configurations can arise from a single DNA sequence.

“A big part of what makes predicting genome structure so complicated is that there’s no single solution that you can aim for,” Schuette says. “No matter where you look in the genome, there’s a distribution of structures, and predicting that very complex, multidimensional statistical distribution is incredibly difficult.”

Quick Analysis

Once trained, the model can generate predictions much faster than Hi-C or other testing techniques.

“While it might take six months of experimentation to get a few dozen structures for a particular cell type, with our model we can generate 1,000 structures for a given area in just 20 minutes on a GPU,” Schuette says.

After training their model, the researchers used it to generate structure predictions for over 2,000 DNA sequences and compared them to experimentally determined structures for those sequences. They found that the structures generated by the model were similar or very similar to those seen in the experimental data.

“We typically look at hundreds or thousands of configurations for each sequence, which allows us to get a good representation of the structural diversity that a particular region can have,” Zhang said. “If we repeat the experiment many times with different cells, we’ll probably get completely different configurations, and that’s what our model is trying to predict.”

The researchers also found that the model was able to make accurate predictions on data from cell types other than the one it was trained on, suggesting that the model could be useful for analyzing how chromatin structure differs between cell types and how those differences affect cellular function. The model could also be used to explore the different chromatin states that may exist within a single cell and how those changes affect gene expression.

“Chromogen provides a new framework for exploring AI-driven genome folding principles, demonstrates that generative AI can link genomic and epigenetic features into 3D genome structures, and points to future work investigating how genome structure and function change in different biological contexts,” said Jean Ma, a professor of computational biology at Carnegie Mellon University who was not involved in the research.

Another application is to investigate how mutations in specific DNA sequences alter chromatin organization, which may shed light on how such mutations cause disease.

“I think there are a lot of interesting questions that can be answered with this kind of model,” Zhang said.

The researchers have made their data and entire model publicly available for others to use.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health.