In biology textbooks, the ER is often described as a distinct, compact organelle located near the nucleus, commonly known to be responsible for protein transport and secretion. In fact, the ER is very large and dynamic, spread throughout the cell, and able to contact and communicate with other organelles. These membrane contacts control various processes such as fat metabolism, glucose metabolism, and immune responses.

Understanding how pathogens manipulate and hijack key processes to further their own life cycle can reveal much about fundamental cellular functions and potentially provide insight into therapeutic options for less well-studied pathogens.

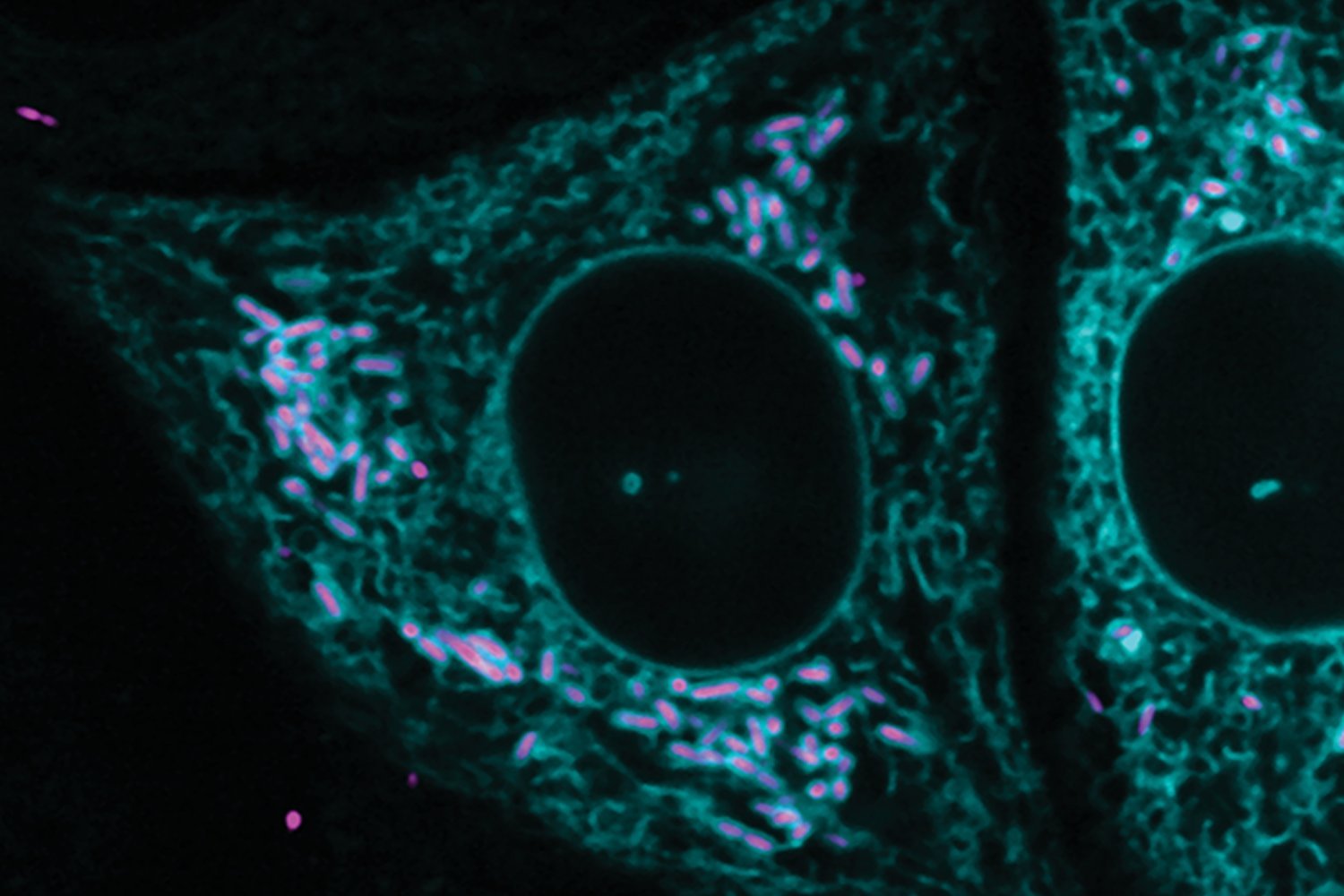

New research from the Lamason Laboratory in the MIT Department of Biology, published in the Journal of Cell Biology, finds that Rickettsia parkeri, a free-living bacterial pathogen in the cytoplasm, can interact extensively and stably with the rough endoplasmic reticulum, forming previously unseen contacts with this organelle.

This is the first known example of direct contact between an intracellular pathogenic bacterium and a eukaryotic biofilm.

The Lamason lab is studying R. parkeri as a model for infection with the more virulent Rickettsia rickettsii , carried and transmitted by ticks , which causes Rocky Mountain spotted fever. If left untreated, the infection can lead to severe symptoms, including organ failure and death.

Rickettsiae are difficult to study because they are obligate pathogens and, like viruses, can only survive and grow inside living cells. Researchers have had to get creative to dissect fundamental questions and molecular drivers in the life cycle of R. parkeri , and there are many unknowns about how it spreads.

Detour to the fork

Lead author Yamilex Acevedo-Sánchez, then a former graduate student in the BSG-MSRP-Bio program, stumbled upon the interaction of R. parkeri with the ER while trying to observe rickettsiae approaching cell junctions .

Current models of R. parkeri spreads from cell to cell by migrating to specialized contact sites between cells, incorporating and spreading into adjacent cells. Listeria monocytogenes, which the Lamason lab also studies, uses its actin tail to push against adjacent cells. In contrast, R. parkeri can form an actin tail but loses it before it reaches the cell junction. Somehow, R. parkeri is able to spread to adjacent cells.

Following an MIT workshop on the little-known functions of the ER, Acevedo-Sanchez developed cell lines to observe whether rickettsiae

Instead, she found that a surprisingly high percentage of R. parkeri was surrounded and contained by the ER, at a distance of about 55 nanometers. This distance is important because membrane contacts for communication between organelles in eukaryotic cells form connections that are 10 to 80 nanometers wide. The researchers ruled out the possibility that what they saw was not an immune response, and that the parts of the ER that interacted with parkeri might still be connected to the broader ER network.

“If you want to learn new biology, look at cells,” Acevedo-Sánchez says. “Manipulating organelles to establish contacts with other organelles could be a great way for pathogens to gain control during infection.”

“A stable connection is undesirable because the ER constantly breaks and recreates connections, lasting for seconds or minutes. It was a surprise to see the ER stably associated with the bacteria. As a cytoplasmic pathogen that resides freely within the cytoplasm of infected cells, it was also a surprise to see that R. parkeri is surrounded by a membrane .”

Small amplitude

Acevedo-Sanchez collaborated with Harvard’s Center for Nanoscale Systems to use a focused ion beam scanning electron microscope to replicate his original observations at a higher resolution. In FIB-SEM, a sample of cells is taken and then a focused ion beam is used to scrape off parts of the cell mass. A high-resolution image is captured for each layer. The result of this process is a stack of images.

From there, Acevedo-Sanchez labeled different regions of the images (mitochondria, rickettsia , ER, etc.), and the machine learning program ORS Dragonfly classified thousands of images to identify those categories. That information is then used to create a 3D model of the sample.

Acevedo-Sánchez notes that less than 5% of R. parkeri form connections with the ER, but a few specific features have been found to be important for R. parkeri infection . R. parkeri can exist in two states: motile, with an actin tail, and non-motile, with no tail. In mutants unable to form actin tails, R. parkeri are unable to progress into neighboring cells, whereas in non-mutants, the proportion of tailed R. parkeri starts at about 2 percent early in infection and never exceeds 15 percent at the peak of infection.

ER interacts exclusively with nonmotile R. parkeri , and the interaction is increased 25-fold in mutants unable to form tails.

Connect

Co-authors Acevedo-Sanchez, Patrick Wojda and Caroline Anderson also investigated how the connection to the ER might be mediated: VAP proteins, which mediate interactions between the ER and other organelles, are known to be hijacked by other pathogens during infection.

During infection with R. parkeri , the VAP proteins are introduced into the bacteria, and their removal reduced the frequency of interactions between R. parkeri and the ER , suggesting that R. parkeri may exploit these cellular mechanisms for its own purposes during infection.

Acevedo-Sanchez now works as a senior scientist at AbbVie, but in the Lamason lab, researchers are continuing to study the molecular factors that may be involved, how these interactions are mediated, and whether contact affects the host or bacterial life cycle.

These potential interactions are particularly intriguing because bacteria and mitochondria are thought to have evolved from a common ancestor, notes lead author Rebecca Lamason, associate professor of biology. The Lamason lab has been studying whether R. parkeri can form mitochondrial-like membrane contacts, but this has not yet been proven. To date, R. parkeri is the only cytopathogenic pathogen that has been observed to behave in this way.

“It’s not just bacteria that accidentally end up in the ER, and these interactions are very stable. The ER is clearly encapsulating the bacteria, and it’s still connected to the ER network,” Lamason said. “It seems to have a purpose, but what that purpose is remains a mystery.”