Researchers at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory have accelerated electrons to high energies in less than a foot using a supersonic gas sheet and two lasers. The breakthrough represents a major advance in laser-plasma acceleration, a promising technology for creating compact, high-energy particle accelerators with potential applications in materials science, particle physics, and medicine. The research will be published in the journal Physical Review Letters .

Scientists have succeeded in accelerating a high-quality electron beam to more than 10 billion electron volts (10 GeV) over 30 cm. The project is led by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) with support from the University of Maryland.

Berkeley Lab’s Center for Laser Accelerators (BELLA), where this research took place, set a world record of 8 GeV electrons per 20 cm in 2019. The new experiment also increased the beam energy, producing high-quality beams at this energy level for the first time, opening the door to future high-performance machines.

We have made the leap from 8 GeV to 10 GeV, but also significantly improved the quality and energy efficiency by changing the technology we use – a key step on the road to future plasma colliders .

Alex Pixley, lead author of the study and research scientist in the Accelerator Technology and Applied Physics Division at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

Plasma is a gaseous mixture of charged particles, including electrons, that is used in Laser Plasma Accelerators (LPAs). By sending intense energy shocks into the plasma for trillionths of a second, researchers can create powerful waves. Like a surfer riding an ocean wave, electrons travel along the crests of these plasma waves, collecting energy as they do so.

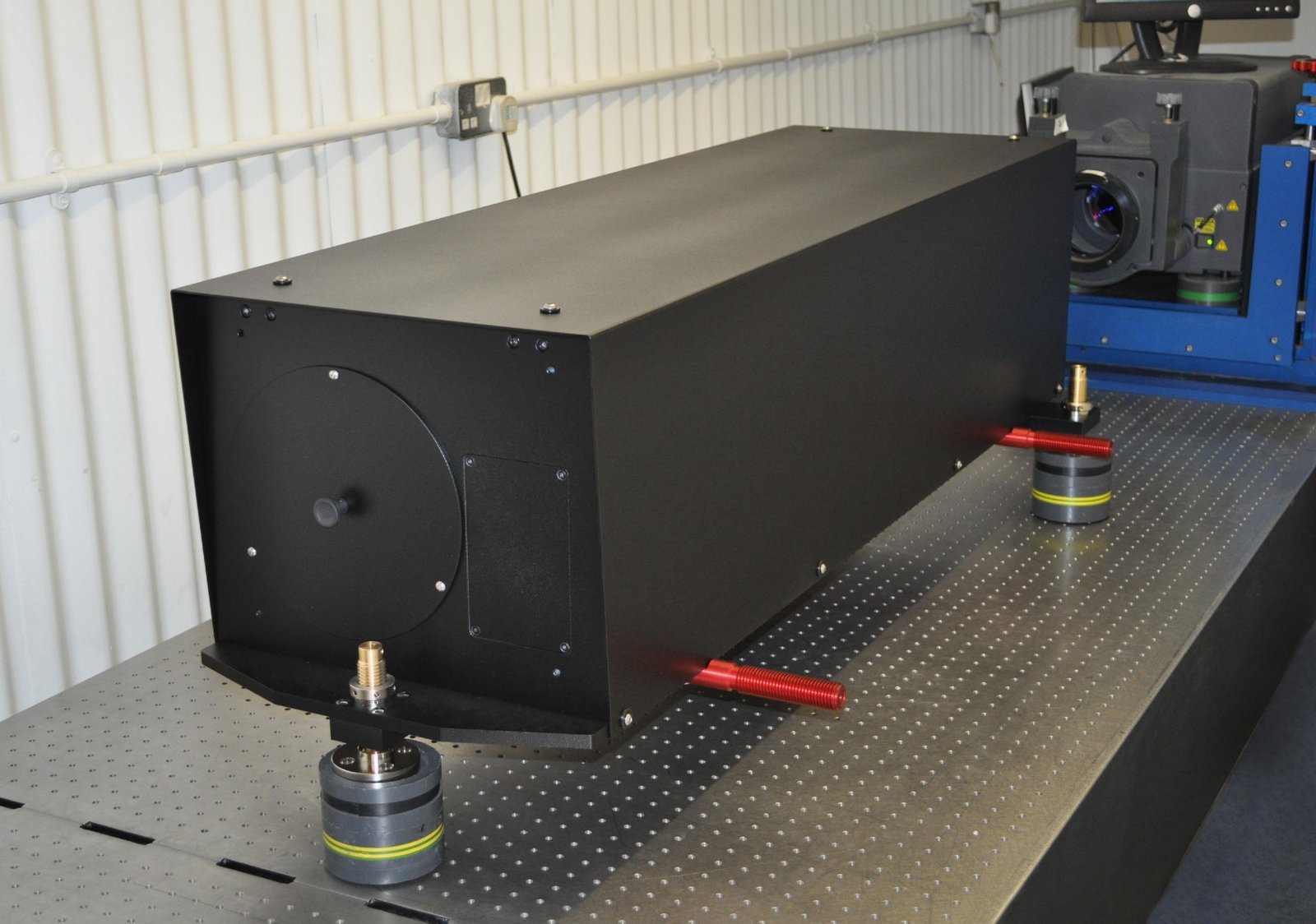

When BELLA’s second beamline is completed in 2022, a dual-laser system will be used to achieve new results. The system’s first laser acts as a drill, heating the plasma to create a channel for the next “control” laser pulse, which accelerates electrons. The plasma channel helps to focus the laser pulse over longer distances and conducts the laser energy in a similar way that a fiber optic cable conducts light.

Previous researchers have used “capillaries” — glass or sapphire tubes of a fixed length — to form the plasma, but to achieve their new results, the team employed a system with multiple gas jets arranged in a row, like the jets in a gas fireplace.

The laser beam passes through the supersonic gas layer generated by the jet, creating a plasma channel. This setup allows the researchers to tune and fine-tune the length of the plasma, allowing them to study the process at different stages with unparalleled precision.

“Before, plasma was essentially a black box: you know what you put in, and you know what comes out at the end. Now, for the first time, we’ve been able to capture what’s happening at each point inside the accelerator, showing frame-by-frame how laser and plasma waves change at high power .”

Carlo Benedetti, Staff Scientist, Accelerator Technology and Applied Physics Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

Benedetti works on the theory and modeling of laser-plasma accelerators.

Comparing models with experiments gives researchers the tools to fine-tune their accelerators and gives them confidence that they understand the physical phenomena at work. The experts used a code created at BELLA called INF&RNO to model the interaction of the laser with the plasma.

The complex calculations were performed at Berkeley Lab’s National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC). New results validate the codes used in these simulations and further strengthen the model.

Another advantage of the air injection system is its resilience: The technique can be scaled to very high repeatability, with no broken parts in the gas layer, something the lab is targeting for particle accelerators and future applications.

The researchers demonstrated that this method produces a “dark-current-free” beam, preventing the inadvertent acceleration of background electrons in the plasma.

If there is dark current, it will absorb the laser energy instead of accelerating the electron beam. Now that we can control the accelerator to prevent unwanted effects, we produce a high-quality beam without wasting energy. That is essential for thinking about the ideal laser accelerator of the future .

Jeroen van Tilborg, Staff Scientist and Deputy Director, Accelerator Technology and Applied Physics Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

Tilborg is in charge of the BELLA test program.

The technology has many potential applications: it could be used to generate particle beams for cancer treatment, for example, or to power free-electron lasers such as atomic force microscopes, which could help develop new materials and understand biological and chemical processes.

“We’ve taken a big step towards enabling applications of these compact accelerators,” said Anthony Gonsalves, an ATAP scientist who leads accelerator research at BELLA. ” For me, the beauty of this result is that we’ve removed the constraints of the plasma geometry that limited the efficiency and quality of the beam. We’ve built a platform that can make significant improvements and we’re poised to realize the amazing potential of laser-plasma accelerators .”

Once upgraded to higher energies, laser plasma accelerators could be used in areas such as fundamental physics. In the short term, LPAs could be used to produce muon beams, which could help image hard-to-access locations such as the inside of nuclear reactors, geological features such as volcanoes and minerals, and architectural structures such as ancient pyramids.

In the longer term, the technology could be used in high-energy particle accelerators that collide charged particles to discover new ones and learn more about the forces that shaped the universe. BELLA researchers are currently working to create these ultra-high-energy machines by combining components of staged accelerator systems.

” Combining these stages provides a realistic pathway towards future particle accelerators that can produce electrons in the 10-100 GeV range and reach 10 TeV [tera electron volts].” “As the laser energy from one stage is used up, we send a new laser pulse, successively increasing the electron energy from one stage to the next,” says Eric Esary, director of the BELLA center.

Researchers need robust diagnostics to develop staging systems that allow them to precisely control timing and synchronize steps that occur in fractions of a second, which will enable them to understand the behavior of plasmas, lasers and electron beams.

“This research has enabled us to increase the particle energy and beam production efficiency for high-quality beams at very short distances, with precision diagnostic techniques that allow for superior laser-plasma control,” said Cameron Geddes, director of Berkeley Lab’s ATAP division. Advances in laser-plasma accelerator technology are recognized as a key goal in both the U.S. Particle Physics Project Priorities (P5) and the Department of Energy’s Advanced Accelerator Development Strategy. This result marks a milestone on our path toward incremental construction of an accelerator that will change the way science is done .”

This research was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science, the High Energy Physics Office and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. This research used the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility.

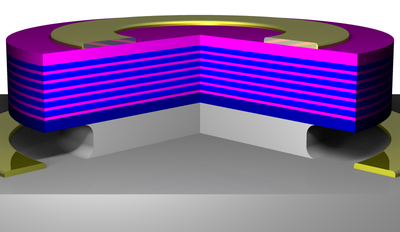

Simulation of a 10 GeV channel-guided laser-plasma accelerator #physics #laser #plasma

In this simulation of the laser-plasma acceleration process created with the INF&RNO code, a laser driver (orange) propagates right through the plasma (blue) and generates a plasma wave. The simulation window moves at the speed of light along with the laser and plasma waves, so they appear to be stationary. After a propagation distance of 30 cm, the laser-ionized electrons (yellow) are captured by the strong electromagnetic field in the plasma and accelerated to energies of up to 10 GeV (yellow beam). Video credit: Carlo Benedetti/Berkeley Lab

sauce:

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory