On your first day on vacation in a new city, you’ll explore a variety of places. While your memories of these places (such as a beautiful garden on a quiet side street) may seem indelible, it may take days before you develop enough of an intuition about the area to guide a new tourist to the same places, and perhaps the cafe you discovered nearby. A new study on mice by neuroscientists at the MIT Picower Institute for Learning and Memory provides new evidence of how the brain forms a cohesive cognitive map of an entire space and highlights the importance of sleep in this process.

Scientists have known for decades that the brain dedicates neurons in a region called the hippocampus to remembering specific locations. The so-called “place cells” are reliably activated when an animal is in a position that the neurons are tuned to remember. But it’s more useful to have a mental model of how they’re all related in a continuous, overall geography than to have specific spatial markers. Such a “cognitive map” was formally theorized in 1948, but neuroscientists still don’t quite understand how the brain builds it. According to a new study published in the December issueCell Reports , this ability may depend on subtle but important changes over several days in the activity of cells that are weakly tuned to individual locations but that increase the robustness and fine-tuning of spatial coding across the hippocampus. Analysis of the study found that during sleep, these “weak space” cells increasingly enrich the activity of the hippocampal neural network, connecting these places to form the cognitive map.

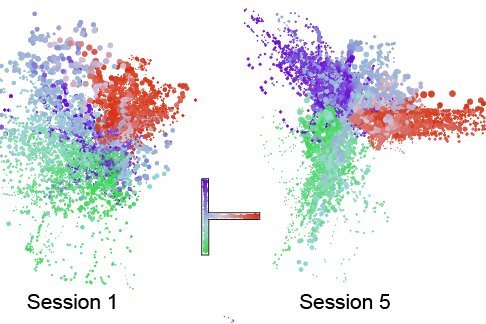

“On day 1, the brain isn’t very good at representing space,” says lead author Wei Guo, a research scientist in the Picower Institute and the lab of lead author Matthew Wilson, the Sherman Fairchild Professor in MIT’s Department of Biology, Brain, and Cognitive Sciences. “Neurons represent individual locations, but when they connect together they don’t form a map. But by day 5, a map forms. If you want to make a map, you need all these neurons working in concert.”

Map the maze with your mouse

To conduct the study, Guo and Wilson, along with lab colleagues Jie “Jack” Zhang and Jonathan Newman, presented mice with simple mazes of different shapes and allowed them to explore freely for about 30 minutes a day over several days. Importantly, the mice were not instructed to learn anything specific through rewards; they just wandered around. Previous studies have shown that mice naturally exhibit spatial “implicit learning” from this kind of reward-free experience after a few days.

To understand how implicit learning occurs, Guo and colleagues visually monitored hundreds of neurons in the CA1 region of the hippocampus, engineering cells to blink when they become electrically activated by the accumulation of calcium ions. The researchers recorded neural firing not only while the mice were actively exploring, but also while they were sleeping. Wilson’s lab revealed that the animals “replayed” past journeys while they slept, refining their memories by essentially dreaming about their experiences.

Analyzing the recordings, they found that place cell activity began immediately and remained strong and unchanged throughout several days of exploration. But this activity alone cannot explain how implicit learning and cognitive maps develop over days. So unlike many other studies in which scientists have focused only on the strong, overt activity of place cells, Guo expanded his analysis to the more subtle, mysterious activity of cells that are not as strongly spatially tuned.

Using a new technique called “diversity learning,” he was able to observe that many of the “weak spatial” cells gradually associated their activity not with location but with patterns of activity among other neurons in the network. As this happened, Guo’s analysis showed, the network encoded a cognitive map of the maze that increasingly resembled the literal physical space.

“Rather than responding to specific locations like strong spatial cells, weak spatial cells are specialized to respond to ‘mental places,’ i.e., specific population firing patterns of other cells,” the study authors wrote. “If the mental field of weak spatial cells consists of two subsets of strong spatial cells that encode separate locations, the weak spatial cells may act as a bridge between these locations.”

In other words, activity in weak spatial cells can link individual locations represented by place cells into a mental map.

The need for sleep

Because research from the Wilson lab and many others has shown that memories are consolidated, refined, and processed through neural activity, including replay, that occurs during sleep and rest, Guo and Wilson’s team sought to test whether sleep is necessary for weak spatial cells to contribute to the implicit learning of cognitive maps.

To achieve this, the researchers had mice explore a new maze twice on the same day, with a three-hour nap in between. Some of the mice were allowed to sleep, while others were not. Mice that were allowed to sleep showed significant improvements in their mental maps, while those that were not allowed to sleep showed no such improvements. Not only does the network encoding of the maps improve, but measurements of the coordination of individual cells during sleep also show that sleep allows cells to become more attuned to both locations and patterns of network activity, known as “mental places” or “fields.”

What is Mind Map?

Guo points out that the “cognitive maps” that mice encode over several days aren’t exact, literal maps of the maze. Rather, they’re like diagrams. Their value is that they provide the brain with a structure that you can mentally explore without being in the physical space. For example, once you’ve created a mental map of the area around your hotel, you can plan your travels the next morning (e.g., imagining yourself buying a croissant from the bakery a few blocks west and eating it on a park bench by the river).

In fact, Wilson hypothesizes that the activity of weak spatial cells may overlay salient non-spatial information that gives the map additional meaning (i.e., the idea of a bakery is not spatial, even if it is closely associated with a specific place). However, the study did not place landmarks in the maze, nor did it test the mice’s specific behavior. But now that the study has established that weak spatial cells make an important contribution to map building, future studies could explore what information they incorporate into animals’ sense of the environment, Wilson says. We seem to intuitively perceive the space we inhabit as more than just a collection of discrete places.

“In this study, we focus on naturally behaving animals and demonstrate that, even in the absence of reinforcement, large population-level neuroplastic changes still occur during free exploration and subsequent sleep,” the authors conclude. “This form of implicit, unsupervised learning constitutes an important aspect of human learning and intelligence and deserves further investigation.”

The research was funded by the Freedom Together Foundation, the Picower Institute and the National Institutes of Health.