Quantum computers promise to solve complex problems many times faster than classical computers, by using the principles of quantum mechanics to encode and process information into quantum bits (qubits).

Qubits are the building blocks of quantum computers. However, one of the challenges in scaling is that qubits are highly sensitive to background noise and imperfections in their control, which introduce errors into quantum operations and ultimately limit the complexity and duration of quantum algorithms. To remedy this situation, researchers at MIT and around the world have continuously focused on improving the performance of qubits.

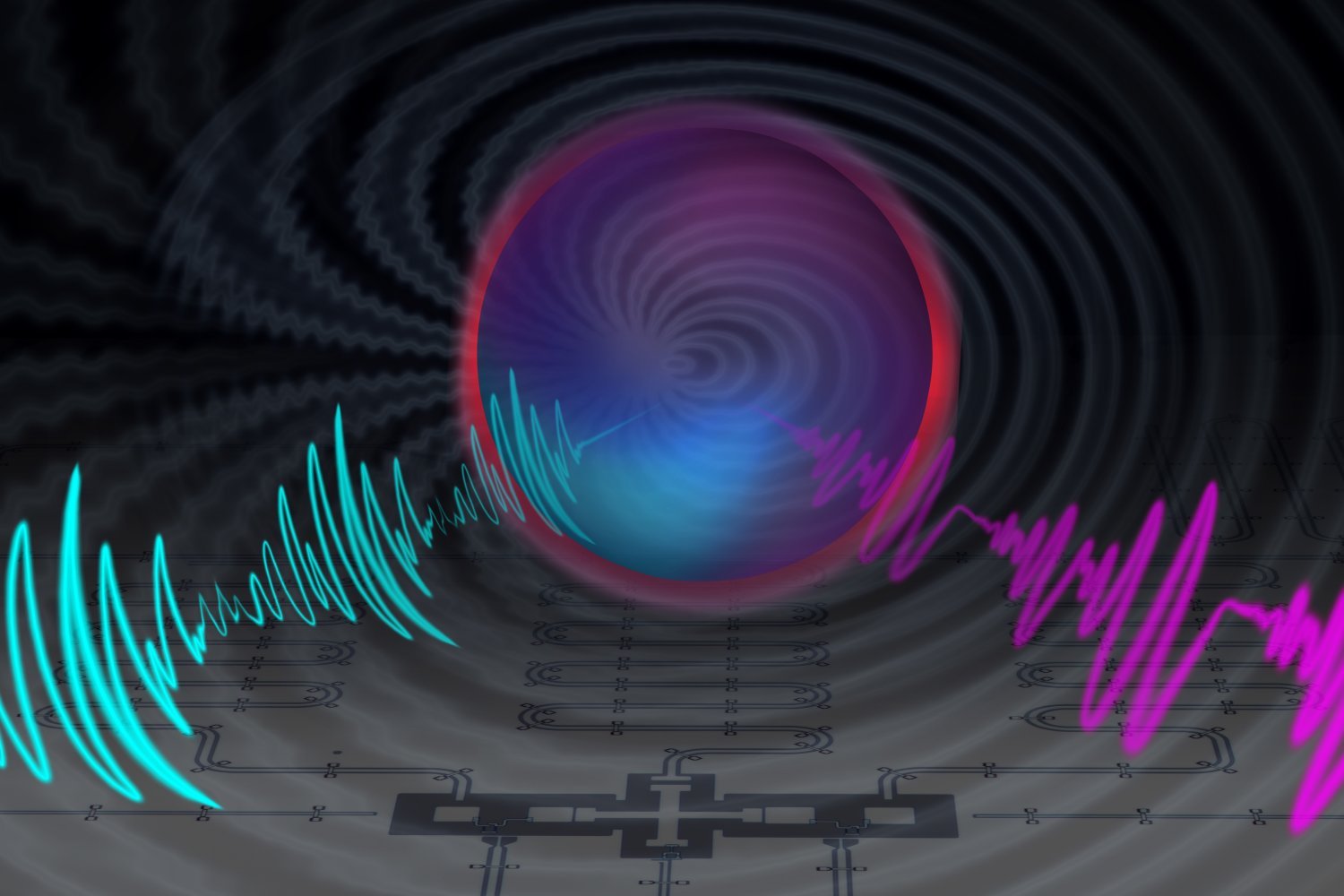

In the new study, using a superconducting qubit called flaxonium, researchers from the MIT Physics Department, the Research Laboratory for Electronics (RLE), and the School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS) developed two new control techniques to achieve a world record qubit fidelity of 99.998 percent. This result joins MIT researcher Leon Ding’s demonstration of two-qubit gate fidelity of 99.92 percent last year.

The paper’s lead authors are David Rower, PhD ’24, a recent physics postdoctoral fellow in the Engineering Quantum Systems (EQuS) group at MIT and now a research scientist at Google’s Quantum AI Lab; Leon Ding, PhD ’23 from EQuS, who now leads the Calibration group at Atlantic Quantum; and William D. Oliver, EECS Henry Ellis Warren Professor of Physics, Director of EQuS, Director of the Center for Quantum Engineering, and Deputy Director of RLE. The article was recently published in the journal PRX Quantum.

Consistency and rollback errors

A major challenge in quantum computing is decoherence, a process in which qubits lose quantum information. In platforms such as superconducting qubits, decoherence prevents the realization of higher fidelity quantum gates.

Quantum computers need to achieve high gate fidelity to perform sequential computations through protocols such as quantum error correction. The higher the gate fidelity, the easier it is to perform practical quantum computations.

To reduce the effects of decoherence, MIT researchers are developing techniques to make quantum gates, the fundamental operations of quantum computers, as fast as possible. But faster gate speeds can introduce another kind of error that arises from inverted spin dynamics due to the way qubits are controlled by electromagnetic waves.

Single-qubit gates are often implemented using resonant pulses that generate Rabi oscillations between qubit states. However, if the pulse is too fast, the “Rabi gate” is not very stable because undesirable errors due to back-rotation effects occur. The faster the gate, the more pronounced the rollback errors become. For low-frequency qubits like flaxonium, the rollback errors limit the fidelity of high-speed gates.

“Eliminating these bugs is an exciting challenge for us,” said Lower. “Leon initially came up with the idea of using circularly polarized microwave drive, which is similar to circularly polarized light, but implemented by controlling the relative phase of the charge drive and the magnetic flux drive of the superconducting qubit. Such a circularly polarized drive should ideally be insensitive to rotation errors.

Ding’s idea quickly worked, but the precision achieved with the circularly polarized drive was not as high as expected from the coherence measurements.

“In the end, we landed on a beautifully simple idea,” says Lower. “If we applied pulses at the right times, we should be able to make the backtracking errors consistent from pulse to pulse. This would make the rollback errors correctable. And even better, they would be automatically taken into account in our periodic RabiGate calibrations.”

They call this idea “matched pulses” because the pulses must be applied at time intervals determined by the qubit frequency and its inverse, the period. Matched pulses are determined simply by the timing constraints and can be applied to a single linear qubit drive. In contrast, circularly polarized microwaves require two drives and additional tuning.

“We had a lot of fun developing this matching technique,” Lower said. “It’s very simple, we understand why it works, and we can transfer it to any qubit that has spin-back error.”

“This project clearly demonstrates that rollback errors can be handled with ease, which is ideal for low-frequency qubits like flaxonium, which are gaining increasing promise for quantum computing.”

Fluxonium’s Promise

Fluxonium is a type of superconducting qubit made up of capacitors and Josephson junctions. But unlike transmon qubits, fluxonium also contains large “superconductors” that, by design, help protect the qubit from environmental noise. This allows logical operations, or gates, to be performed with greater precision.

However, despite its high coherence, fluxonium qubit frequencies tend to be lower and gates proportionally longer.

“Here, we have demonstrated the fastest and highest-fidelity gates of all superconducting qubits,” Ding said. “Our experiments demonstrate that fluxonium is a qubit that not only supports exciting physical discoveries, but also offers exceptional engineering performance.”

With further research, we hope to discover new limits and create even faster, higher fidelity gates.

“Inverse spin dynamics has been understudied in the field of superconducting quantum computing because the spin-wave approximation works well in conventional regimes,” Ding said. “Our paper shows how to precisely calibrate high-speed low-frequency gates, where the rotating-wave approximation does not hold.”

Collaboration between physics and engineering

“This is a great example of the kind of work we want to do at EQuS, leveraging fundamental concepts from both physics and electrical engineering to achieve better results,” Oliver said. “It builds on our previous work on non-adiabatic qubit control and applies it to a new qubit, fluxonium, making a beautiful connection with counter-rotation dynamics.”

The science and engineering team achieved high fidelity in two ways: First, they demonstrated “coherent” (synchronized) nonadiabatic control that goes beyond the standard “rotating wave approximation” of standard Rabi techniques, an idea that powered the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physics for ultrafast “attosecond” light pulses.

They then demonstrate this using a circularly polarized analog signal: instead of a physical electromagnetic field with a polarization vector rotating in real xy space, they created a synthetic version of circular polarization using the xy space of qubits (corresponding in this case to magnetic flux and charge).

This result was achieved by combining an existing novel qubit design method (Fluxonium) with the application of advanced control methods to understand the underlying physics.

The work establishes a simple strategy for mitigating back-to-back effects from strong dynamics in circuit quantum electrodynamics and other platforms that is platform-independent and does not require additional calibration overhead, which the researchers hope will aid efforts to achieve high-fidelity control of fault-tolerant quantum computers.

Oliver added, “Given the recent announcement that Google’s Willow quantum chip was the first to demonstrate above-threshold quantum error correction, this is a timely achievement, and we intend to continue to push performance even further. As qubit performance improves, the cost required to implement error correction will also decrease.”

Other researchers on the paper are Helin Zhang, Max Hays, Patrick M. Harrington, Ilan T. Rosen, Simon Gustavsson, Kyle Serniak, Jeffrey A. Grover, and Junyoung An of RLE, who also work in EECS, and Jeffrey M. Gertler, Thomas M. Hazard, Bethany M. Niedzielski, and Mollie E. Schwartz of MIT Lincoln Laboratory.

This research was funded in part by the U.S. Army Research Office, the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science, the National Center for Quantum and Information Science Research, the Quantum Advantage Co-Design Center, the U.S. Air Force, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence and the National Science Foundation.