More efficient artificial pollination methods could one day enable farmers to grow fruits and vegetables inside multi-story warehouses, increasing yields while reducing some of agriculture’s harmful environmental impacts.

To make this idea a reality, MIT researchers are developing robotic insects that could one day fly out of mechanical beehives to perform precise, on-the-spot pollination. But when it comes to durability, speed, and maneuverability, even insect-sized robots can’t match natural pollinators like honeybees.

Now, inspired by the anatomy of these natural pollinating insects, researchers are improving their designs to create flying robots that are smaller, more agile and more durable than previous versions.

The new robot can hover for about 1,000 seconds, 100 times longer than its predecessor. The robot insect weighs less than a paper clip, can fly much faster than similar robots, and can perform acrobatic maneuvers such as double somersaults.

This innovative robot is designed to increase precision and agility in flight while minimizing mechanical stress on the curvature of its artificial wing, resulting in faster maneuvers, greater durability and a longer lifespan.

The new design gives the robot enough space to carry small batteries and sensors, allowing it to venture out of the lab on its own.

“The flight distance we’ve demonstrated in this paper is probably longer than the combined flight distances our field has ever managed to accumulate with these robotic insects,” said Kevin Chen, associate professor in the School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS), director of the Laboratory of Soft Robotics and Microfabrication in the Research and Electronics Engineering (RLE), and lead author of the open-access paper on the new design. “The increased lifetime and precision of this robot bring us closer to some very interesting applications, such as assisted pollination.”

Chen contributed to the paper along with EECS graduate students Suhan Kim and Yi-Hsuan Hsiao, as well as fellow EECS graduate student Zhijian Ren and summer visiting student Jiashu Huang. The research was published today in Science Robotics .

Performance improvements

Previous versions of the robotic insect were made up of four identical pieces, each with two wings, assembled into a rectangular device about the size of a microcassette tape.

“But no insects have eight wings. “In our previous designs, the performance of the individual units was always better than the performance of the assembled robot,” Chen said.

This loss of performance is due in part to the arrangement of the wings: as they flap, they blow air into each other, reducing the amount of lift they can generate.

The new design cuts the robot in half, with four identical units each equipped with wings that flap away from the robot’s center, helping to stabilize them and increase lift. With half the number of wings, this design also frees up space for the robot to carry electronics.

Additionally, researchers have developed more complex actuation systems that connect the wings to actuators and artificial muscles that help them flap. These more durable actuation systems require longer wing hinge designs, which reduce the mechanical stresses that limited the durability of previous versions.

“Compared to our older robots, we can now generate three times the control torque, enabling much more sophisticated, very precise path-finding flight,” Chen said.

But even with these design improvements, a gap still exists between the best robotic insects and reality: honeybees, for example, have only two wings but are capable of fast and highly controlled movements.

“A honeybee’s wings are finely controlled by very sophisticated sets of muscles. That level of fine-tuning really excites us, but we can’t replicate it yet,” he said.

Less stress, more power

The movement of the robot’s wings is controlled by artificial muscles. These tiny, soft actuators are made from a layer of elastomer sandwiched between two extremely thin carbon nanotube electrodes, then rolled into a soft cylinder. The actuators rapidly compress and expand, generating the mechanical force that makes the wings flap.

With previous designs, when the actuator movements reached the extremely high frequencies needed for flight, the devices would often begin to distort, reducing the robot’s power and efficiency. The new gearbox prevents this warping motion, reducing stress on the artificial muscles and allowing them to exert more force to flap the wings.

Another new design includes a long wing hinge that reduces torsional stress during flapping motion. Making the hinge, which is about 2 cm long and just 200 microns in diameter, was one of the biggest challenges.

“If a small alignment issue occurs during manufacturing, the wing hinge will be tilted rather than at a right angle, which will affect the wing kinematics,” Chen said.

After much experimentation, the researchers perfected a multi-step laser cutting process that allowed them to precisely manufacture each wing hinge.

With all four components installed, the new robotic insect can hover for more than 1,000 seconds, or about 17 minutes, without losing flight precision.

“When my student Nemo did that flight, he said it was the slowest 1,000 seconds he had ever experienced in his life. This experiment was really stressful,” Chen said.

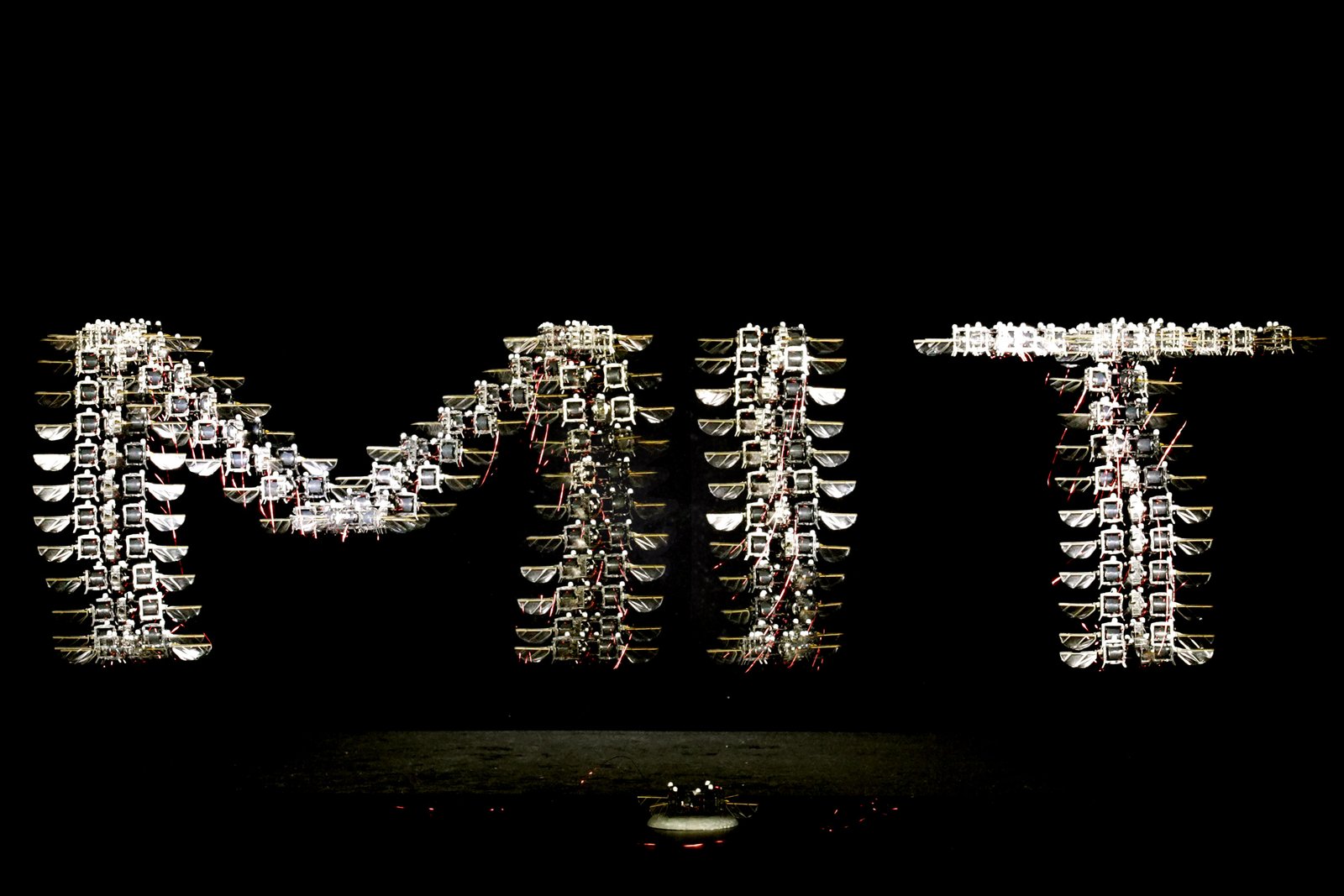

The new robot also reached an average speed of 35 centimeters per second while performing double backflips and somersaults, the fastest flying speed reported by researchers. It can also accurately trace a trajectory that spells out MIT.

“This is an incredibly exciting result because we’ve finally demonstrated the ability to fly 100 times farther than anyone else in the field,” he said.

Going forward, Chen and his students hope to explore how far they can push this new design, aiming for flight times of more than 10,000 seconds.

They also hope to improve the robot’s precision so that it can land and take off from the center of the flower. In the long term, the researchers hope to equip the flying robot with batteries and small sensors so that it can fly and navigate outside the lab.

“This new robotics platform is a significant achievement for our team and leads to many exciting directions. For example, integrating sensors, batteries and computing capabilities into this robot will be a focus over the next three to five years,” Chen said.

The research was funded in part by the National Science Foundation and a Mathworks Fellowship.